It’s the penultimate day of half term and I have just asked my Year 11 crew, “How has the first week back helped you this half term?” A week in which students undertook a mini-expedition, “We Are G28,” with the question: How can we nurture the best version of our future selves? They completed a high ropes course, a cooking challenge, a session on learning and self-regulation, and an academic challenge. Their responses were telling: “I am just more aware of what I need to do and how it’s going;” “I am better at just getting things done—not because I am more motivated—I just know it needs to be done and I get it done;” and, “I am more organised, and that helps me keep on top of my extended study and get a chance to revise.”

All of which points to an increasing ability to self-regulate. No one is claiming that this week developed this; students learn this as they mature, and our expeditionary curriculum has many (amazing) experiences for students to grow and develop these skills. However, this week did have a significant taught element that seems to have crystallized many students’ capacity for self-regulation.

So, what did we do?

In the case study, “How can I become a more independent learner?” We learned that becoming an independent learner is not just about doing work alone; it’s about taking ownership of our education by consciously thinking about how we learn and actively seeking ways to improve. This activity laid the foundation for the entire expedition, helping us understand the core principles behind effective learning.

We introduced the term “self-regulated learner” and began with a self-assessment questionnaire where we scored ourselves to gauge our current learning habits. It was a great way to honestly look at our strengths and areas for improvement. We explored what such a learner might know, do, and be like, and how they might think. We learned that a self-regulated learner “monitors, directs, and regulates actions toward goals of learning new information, expanding expertise, and self-improvement.”

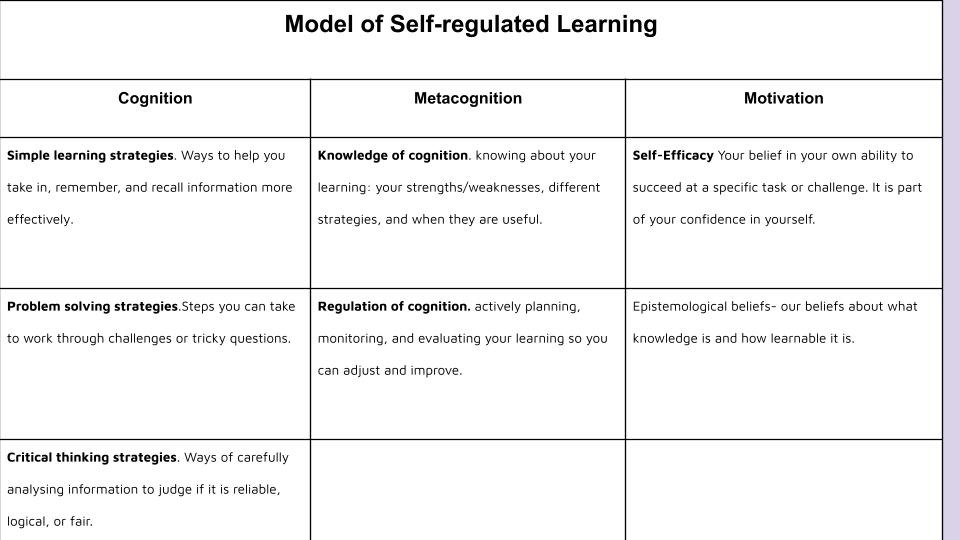

Introducing a model of Self Regulation.

We used Pintrich’s model of Self-Regulation to break this down into “cognition”—the mental process of acquiring knowledge—and “metacognition,” which is being aware of our own thinking and learning to make better decisions, and “motivation”—a blend of our feelings of self-efficacy and resilience, our view of learning, and how we set and use goals. Asking a simple question of “how would you feel if you had to teach a class of Japanese students how to make a cake in fluent Japanese?” revealed how we change our goals to make them more manageable and build confidence levels.

Important distinctions were made between “Knowledge about Cognition” and “Regulation about Cognition.” This provided students with a simple dichotomy between knowing how to learn and study, and how to make good decisions while studying, based on an understanding of planning, monitoring, and regulation.

Making pledges.

This ultimately led us to making pledges to become better learners, not just for this week but for the year ahead. Students started by picking three statements from the questionnaire that we want to improve upon and creating a plan with short and long-term goals. This personalized approach empowers us to take concrete steps towards becoming more independent and effective learners.

| Name: |

| Goal 1: carefully consider whether the materials or methods im using are actually useful and if im just rehashing something i already know |

| Plan: provide reason for why I’m doing what I’m doing and keep a list of what knowledge im confident in and what needs further consolidation |

| Goal 2: ensure im understanding full concepts and not forgetting what ive previously learned |

| Plan: before starting a new activity or creating a new resource, write a summary paragraph of whatever the last thing i learned was |

| Goal 3: decide which revision methods work best for me depending on the subject rather than just repetitively exhausting the same basic method |

| Plan: attempt to memorise the same knowledge from multiple different methods and resources and decide which works best (eg. put maths formulas into a mindmap, flashcards, a quiz and a list |

These pledges and Pintrich’s model of self-regulation were the backbone of all other experiences and gave us common language and understanding to talk about how we operate as learners and how we might need to be to grow our capacities.

The power of Crew.

Our next case study asked, “Why is crew important to my resilience?” To do this, students needed to explore their comfort zone, and so we traveled to North Yorkshire for a high ropes course, where we navigated obstacles relying on our crew. My crew had a wide range of confidences and abilities, but regardless of this, every student experienced a moment where they thought they could not do something. Where the fear kicked in and any notion of a plan or strategy was simply alien. This was when the power of Crew took over. This taught us that resilience isn’t a solitary trait but a collective strength, and that a strong crew provides a vital support system for overcoming adversity. This experience reinforced the importance of our group bonds and built the resilience needed for future challenges.

The next case study asked, “What can cooking tell me about learning?” It was set as a small group challenge, using the “critical skills model” as a starting point. Groups planned, prepared, and cooked a two-course meal. This involved managing a budget, researching recipes, dividing tasks, and presenting a final dish with a menu card including costs and nutritional information. What the focus really was, was a way to explore the ideas we had learned about Self-regulated Learning, and the Planning, Monitoring, and Regulation part of “metacognition,” and a further reinforcement of our crew, as success requires clear communication and efficient teamwork.

The final case study was very much a culmination of the previous experiences and a chance to apply our newly made pledges. It asked the question: How can I improve my academic performance?

Again, using the critical skills approach to set a challenge, each student chose a difficult curriculum topic and worked to master it using new knowledge of self-regulated learning. Namely, setting manageable goals, considering strategy, learning strategy, and then monitoring and regulating our attention throughout. It culminated in each crew member presenting their progress to our crew, which showed us we were capable of performing at a high level, proving that we can overcome academic obstacles through effort and effective learning strategies. This activity linked theoretical skills to practical application, demonstrating the tangible benefits of a focused, self-regulated approach to studies.

Letter to My Future Self.

At the end of each day, debriefing sessions allowed us to reflect on what the activities taught us about nurturing our future selves, and this culminated in a “Letter to My Future Self.” This final task made the learning tangible, creating a time capsule of our growth to reflect upon in the future. Students wrote in confidence that this final task was personal. It could be shared if they wanted, but it was for them—a chance to be honest with themselves, engage in positive self-talk, and aspire to the best version of themselves.